A hundred years on: the Volksbund lays to rest the remains of German First World War soldiers in Langemark

Foto: Simone Schmid

Foto: Simone Schmid

Earlier, the President of the Volksbund, Wolfgang Schneiderhan, alongside mayor of Langemark-Poelkapelle Lieven Vanbellegheim and the German ambassador to Belgium, Martin Kotthaus, laid wreaths in the municipalities of Langemark and Wijschate in order to commemorate the many victims of the destruction of these villages in the war. In his welcome speech, the mayor thanked the Volksbund, and in summing up declared that “... a hundred years on, the traces of this war remain.”

The dead were found during archaeological excavations at former position “Hill 80” near Wijtschate (Heuvelland)

People came together from all over Europe to recover these dead. In a transnational crowdfunding project, voluntary helpers under scientific supervision recovered the bodies of German, British, French and South African personnel and documented their finds. The Volksbund supported the project to the tune of 25,000 euros.

Foto: Simone Schmid

Foto: Simone Schmid

Simon Verdegem, the director of exhumation, emphasised the particular importance of this transnational project: “Following the burial of the British soldiers yesterday, we have come together today to give a final and dignified resting place to the German soldiers of Hill 80 and comrades of theirs who were found in other locations. I venture to believe that the knowledge that individuals from all over the world have pooled their resources to recover the remains of those soldiers will enable them to find peace. This can be seen as a symbol of peace and reconciliation.”

Even today, the Volksbund is still discovering war dead

Foto: Simone Schmid

Foto: Simone Schmid

The Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge (German War Graves Commission) was founded in 1919 with the mission of looking for and finding soldiers who had fallen in the First World War and giving them a dignified burial. A hundred years later, this is still one of the commission’s core tasks. It seeks, finds and lays to rest the war dead – between 20,000 and 30,000 a year. Currently, the Volksbund is discovering most of the fallen of the Second World War in eastern Europe. It is therefore serendipitous that in this hundredth year of its existence, it should be burying nearly a hundred fallen of the First World War.

And Langemark itself is of special significance as a place abused twice over by German nationalist propaganda. In November 1914, the German high command claimed that youth regiments had taken the enemy positions with the German national anthem on their lips. This was simply untrue. The soldiers had been driven into the enemy machine gun fire. In spite of the heavy loss of life this militarily pointless manoeuvre entailed, the National Socialists, in order to once again drive young men to their deaths in the next war, fashioned from it the myth of a generation of young people willing to make the ultimate sacrifice.

“At this cemetery”, said Wolfgang Schneiderhan in his remembrance speech, “we see the inscription: ‘Germany must live even if it means we must die’, a line from the poem ‘Soldatenabschied’ (The Soldier’s Farewell) of 1916 by Heinrich Lersch. Everything is wrong about this line. Germany, Belgium, Poland, Europe – they will only live by not making war against each other and instead peacefully shaping a tomorrow together.”

Foto: Simone Schmid

Foto: Simone Schmid

Martin Kotthaus, ambassador of the Federal Republic of Germany to the Kingdom of Belgium, recalled the suffering of the dead who repose in Langemark. “Their gravestones are symbols of unfulfilled dreams, untrodden paths and unrealised life plans. When we read the journal entries written by soldiers on both fronts in the war, we encounter a common language of suffering. In their fears, in their sorrow, in their compulsions and in their unfulfilled hopes, the young men of all the armed forces, across national boundaries and regardless of friendship or hostility, resembled one another so greatly, so closely.”

War often means that old men talk and young men die

Foto: Simone Schmid

Foto: Simone Schmid

Through Langemark, the cemetery is linked to school students, to the youth. This makes it all the more fitting that children and young people should participate in this remembrance ceremony. In their performance, the pupils of Langemark’s Free Primary School exhorted in various languages: “Sowing-seed must not be ground!” Pupils of the Krollbachschule in Hövelhof enacted a dialogue about whether this war of yesteryear is still relevant to the youth of today. Yes, they established, as wars are currently being fought in 24 different countries. Mazhar explains to a fellow pupil why he had to flee Afghanistan: “My father was a policeman and was supposed to work for the IS.” Their conclusion: “What a stroke of luck, to live in peace.”

Albert Schweitzer medal awarded to director of exhumation Simon Verdegem and photographer Johan Pauwels

Foto: Simone Schmid

Foto: Simone Schmid

Johan Pauwels (left) has for many years been taking high-quality photographs, on a voluntary basis, of war graves sites in numerous different countries and in the cemeteries of various nations.

Foto: Simone Schmid

Foto: Simone Schmid

The remembrance ceremony at the war graves site concluded with ecumenical prayers, the burial of the coffins and the laying of wreaths.

International rather than nationalistic: in Langemark, the way people think has changed

Today, in this region where wars once raged, people gather from all over Europe: in order to remember, and motivated by an interest in their shared European history. In Langemark a change in the way people think can be seen. Ever since the early 1950s, children and young people have been coming together at the Volksbund’s youth meeting and educational centre in Lommel to learn from the past for the sake of the future.

More than 44,000 war dead from the First World War, some 25,000 of them in communal graves, repose in the war graves site in Langemark. The Flemish government provides financial support for the maintenance and restoration of the war graves sites of Menen, Vladslo, Langemark and Hooglede, which have, for the past eight years, been protected historical sites. In Belgium alone there are 134,000 German military graves from the First World War.

Country representative honoured

Foto: Simone Schmid

Foto: Simone Schmid

For his services as country representative for Belgium, Yvan Vandenbosch was presented by the President of the Volksbund, Wolfgang Schneiderhan, with the Volksbund Cross of Honour (gold). After 13 years, he is now handing over to Erik de Muynck.

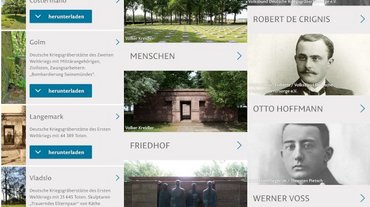

Digital cemetery app

Foto: Simone Schmid

Foto: Simone Schmid

An important role in the memorial site’s transformation into a place of learning is also being played by the “Digitaler Friedhof” (Digital cemetery) app. Visitors to Langemark Cemetery can use the app, for example, to find out all sorts of useful and interesting facts about the cemetery’s history the graves, the Battle of Ypres – and of course the myths.